For millennia, humanity has been captivated by the mystery of death and what comes after. Across ancient cultures, the afterlife was more than a philosophical pondering; it was an integral part of their understanding of existence. For the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Mesopotamians, death wasn’t an ending but a transition. These civilizations wove rich tapestries of myths, rituals, and cosmological beliefs around the afterlife, reflecting their hopes, fears, and spiritual aspirations.

Join me as I take you on a tour of these three ancient cultures’ interpretations of the afterlife. We’ll traverse the sands of Egypt, the shores of the Aegean, and the fertile plains of Mesopotamia to uncover how each civilization viewed life after death.

The Egyptian Afterlife: Journey Through the Duat

Death as the Beginning

For the ancient Egyptians, life was a mere precursor to eternity. The afterlife was not just a belief; it was an expectation, shaping daily life, morality, and even architecture. Death was seen as a journey—a perilous adventure through the Duat, the underworld, where one would face trials, temptations, and divine judgment.

But to understand Egyptian beliefs, we must start with the core concept of ma’at. Ma’at represented truth, balance, and cosmic order, principles that governed both the living and the dead. A person’s ability to achieve a blissful afterlife hinged on their alignment with ma’at during their earthly existence.

The Role of the Ka, Ba, and Akh

Central to the Egyptian concept of the afterlife were three spiritual components: the Ka, Ba, and Akh. The Ka was a person’s life force or spiritual twin, which continued to exist after death. It needed sustenance, which is why food and drink offerings were left in tombs. The Ba, often depicted as a bird with a human head, represented the personality and individuality of the deceased, capable of traveling between the living world and the afterlife. When the Ka and Ba were reunited in death, they formed the Akh, a transfigured spirit that could dwell in the realm of the gods.

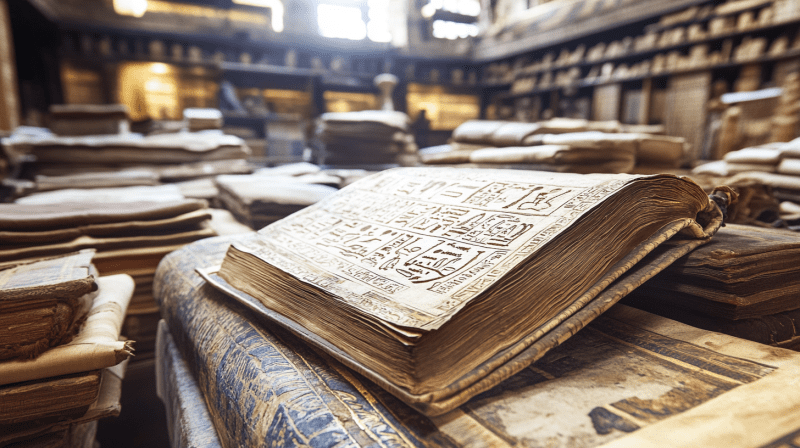

The Book of the Dead and the Journey Through the Duat

The journey into the afterlife was fraught with challenges. The deceased would encounter many dangers in the Duat, from fiery lakes to serpent demons. To navigate this perilous realm, Egyptians turned to a guidebook of sorts—the Book of the Dead. This collection of spells, prayers, and incantations was intended to help the dead pass through the obstacles of the underworld and emerge victorious in the Hall of Judgment.

The Book of the Dead is perhaps most famous for its depiction of the “Weighing of the Heart” ceremony. In the Hall of Judgment, the deceased’s heart was placed on a scale opposite the feather of Ma’at. Ammit, a terrifying creature that is a mix of a lion, hippopotamus, and crocodile, would eat the heart if it was heavier than a feather due to sin. However, if the heart was light, the deceased could enter the Field of Reeds—an eternal paradise mirroring the best aspects of earthly life, where they could farm, fish, and enjoy a peaceful existence.

Tombs and Preparation for Eternity

The ancient Egyptians placed immense importance on tombs as preparation for the afterlife. The grandeur of tombs, such as the pyramids and the Valley of the Kings, reflected the Egyptian belief that the tomb was a house for eternity. Within, bodies were meticulously mummified to ensure the soul’s return to the body after death. Surrounding the tombs were all the provisions necessary for a comfortable afterlife—food, clothing, furniture, and even shabti figures to serve the deceased in the afterlife.

Death, in Egypt, was not something to fear but an inevitable passage to eternal life. Yet, this eternity was not guaranteed; it depended on living in accordance with ma’at and passing the divine tests of the Duat.

The Greek Afterlife: Shadows in the Underworld

Hades: The Lord of the Dead

The Greeks had a more somber view of the afterlife compared to the Egyptians. The stern god Hades is in charge of the Underworld, where the soul would depart after death. Unlike the Egyptian paradise of the Field of Reeds, the Greek Underworld was not a place of reward but a shadowy continuation of existence, where souls led a bleak and uneventful existence.

When a person died, they would be escorted to the Underworld by Hermes, the messenger of the gods. Their first task was to cross the River Styx, guided by Charon, the ferryman, who required payment for safe passage—hence the Greek practice of placing a coin in the mouth of the deceased.

The Geography of the Underworld

The Greek Underworld was not a monolithic place but a vast, multi-layered realm with different regions for different souls. The most common fate was to dwell in the Fields of Asphodel, a dreary and monotonous plain where most souls would wander, their memories of life slowly fading.

But the Underworld also had regions for the virtuous and the wicked. The Elysian Fields, reserved for heroes and those favored by the gods, offered an afterlife of eternal bliss. Here, the air was always sweet, and the landscape lush and verdant, reminiscent of an idealized version of the mortal world. Great warriors like Achilles and poets like Orpheus could find eternal peace in Elysium.

In stark contrast lay Tartarus, the prison of the damned, where souls who had committed the most egregious offenses were punished. Figures like Sisyphus, condemned to eternally roll a boulder uphill, and Tantalus, doomed to eternal hunger and thirst, were classic examples of the severity of Tartarus. The Titans—primordial gods that Zeus had overthrown—lived in this region in addition to serving as a place of punishment for mortals.

The Role of Judgement

Like the Egyptians, the Greeks also believed in divine judgement. Three infernal judges—Rhadamanthus, Minos, and Aeacus—would decide a soul’s fate after it entered the Underworld. However, unlike the Egyptian Weighing of the Heart, the Greeks did not have a detailed code of ethics tied to the outcome of judgment. Instead, the judgment seemed to depend on a person’s overall deeds, with the most heroic or treacherous receiving special treatment in Elysium or Tartarus.

Reincarnation and the Cycle of Souls

One of the most fascinating aspects of Greek afterlife beliefs is the concept of reincarnation, particularly in the later philosophical traditions. Many Greeks held the view that after spending time in the Underworld, souls would reincarnate in new bodies, drawing inspiration from thinkers like Pythagoras and Plato. Plato’s famous work, The Republic, introduces the Myth of Er, where souls are given the chance to choose their next life, often based on the lessons learned from their previous existence. This belief in the cycle of rebirth was not universally accepted but became a prominent feature of Greek spiritual thought.

The Mesopotamian Afterlife: The Land of No Return

A Gloomy Destiny

In sharp contrast to the Egyptian vision of paradise and even the Greek tiered afterlife, the Mesopotamians viewed the afterlife as an inevitable descent into a dark, dreary underworld known as Kur or Irkalla. This was not a place of reward or punishment; rather, it was a dismal and gloomy realm where all souls, regardless of their deeds in life, would reside.

Death was considered an unfortunate but inescapable fate, and the underworld was governed by Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Dead. Once a person entered the Land of No Return, there was no escape. Life in the Mesopotamian afterlife was bleak, described as a shadowy existence where the dead ate clay and dust, stripped of all earthly comforts and joys.

Descent Into the Underworld

Mesopotamian myths, like the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Descent of Inanna, give us vivid insights into their understanding of death. In The Descent of Inanna, the goddess Inanna (or Ishtar) descends into the underworld to challenge her sister, Ereshkigal. However, upon her arrival, she is stripped of her power and trapped in the underworld, signifying the irreversible nature of death in Mesopotamian culture. The myth highlights the dangers and inevitability of the afterlife, even for gods.

Funerary Practices and the Care for the Dead

Despite the grim outlook on the afterlife, the Mesopotamians placed great importance on proper funerary practices. Without the correct burial rites, it was believed that the dead could become restless spirits, or etimmu, wandering the earth and causing harm to the living. Therefore, ensuring that a person was buried correctly, with offerings and prayers, was crucial for both the living and the dead.

The Pit of Souls: A Unchanging Underworld

Unlike the Egyptian vision of an evolving journey or the Greek judgment that placed souls in specific afterlife realms, the Mesopotamian afterlife was static. The dead remained in the underworld for eternity, experiencing neither joy nor punishment but rather a state of perpetual monotony. This view likely influenced their greater emphasis on life and material success in the earthly realm since there was no hope for a paradisiacal afterlife.

A Journey of Beliefs Across Cultures

The ancient cultures of Egypt, Greece, and Mesopotamia offer fascinating glimpses into how humans have grappled with the concept of death and the afterlife. The Egyptians, with their optimistic vision of paradise, devoted their lives to ensuring a smooth passage to the afterlife. The Greeks, while offering paths to both reward and punishment, often viewed death as a continuation in a shadowy, distant realm. Meanwhile, the Mesopotamians saw the afterlife as an unchangeable destiny, a reflection of life’s inevitable end.

Each of these cultures developed rich mythologies and elaborate rituals surrounding death, shaping not only their spiritual beliefs but also their daily lives. Their views on the afterlife—whether as a place of judgment, eternal paradise, or endless darkness—provide us with profound insights into how they understood the mysteries of existence, and perhaps, how we still grapple with those mysteries today.

References

- Assmann, Jan. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press, 2005.

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Taylor, John H. Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. The British Museum Press, 2001.

- Vernant, Jean-Pierre. Mortals and Immortals: Collected Essays. Princeton University Press, 1991.