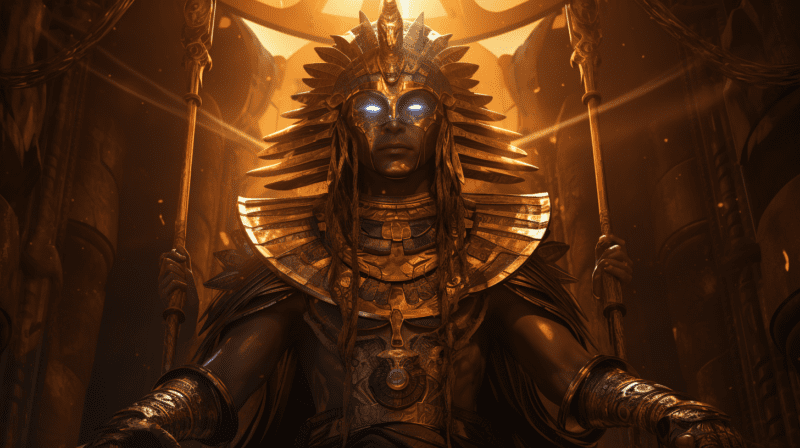

In the vast tapestry of ancient mythology, few figures are as enigmatic and fascinating as Ereshkigal, the formidable Queen of the Underworld in Mesopotamian mythology. Her story is a rich blend of power, mystery, and tragedy, providing a deep and complex portrait of a deity who rules over the dark and shadowy realm beneath the earth.

The Mythological Landscape

To understand Ereshkigal, one must first grasp the context of the Mesopotamian pantheon. Ancient Mesopotamia, comprising modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, and parts of Syria, Iran, and Turkey, was home to a civilization that thrived for millennia. The Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians contributed to a rich mythological tradition that shaped their understanding of the world and the divine.

Ereshkigal’s domain, the Underworld (known as Irkalla or Kur), was a place of shadows and eternal silence, starkly contrasting with the vibrant, bustling life above. It was where the souls of the dead resided, a grim abode governed by strict rules and dire consequences for those who dared to defy its order.

Ereshkigal’s Origins

Ereshkigal’s name, translating to “Lady of the Great Place,” hints at her lofty and fearsome position. Her origins are somewhat shrouded in mystery, but she is generally considered a daughter of Anu, the sky god, making her one of the elder deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon. This lineage places her among the ranks of the most powerful gods and goddesses, with dominion over one of the most feared and respected realms.

Her siblings include Inanna (known as Ishtar in Akkadian mythology), the goddess of love, beauty, and war, and Utu (or Shamash), the sun god. The dichotomy between Ereshkigal and Inanna is particularly striking, as they represent two extremes of existence: life and death, light and darkness, love and fear.

The Descent of Inanna

One of the most well-known stories involving Ereshkigal is the epic “Descent of Inanna.” This tale not only underscores Ereshkigal’s power but also provides a poignant exploration of the themes of death and rebirth.

Inanna, driven by a desire to expand her power and perhaps by sheer curiosity, decides to visit her sister Ereshkigal in the Underworld. Before descending, she instructs her loyal servant, Ninshubur, to seek help from the gods if she does not return.

Inanna’s journey is perilous. She must pass through seven gates, each time shedding a piece of her regal attire, symbolic of her shedding her earthly powers and status. By the time she reaches Ereshkigal’s throne room, she is naked and vulnerable.

Ereshkigal, far from being welcoming, is furious at this intrusion. She commands her attendants, the Anunnaki, to seize Inanna and strike her dead. Inanna’s lifeless body is then hung on a hook, a stark reminder of Ereshkigal’s absolute authority over the dead.

The Dual Nature of Ereshkigal

Ereshkigal’s reaction to Inanna’s descent can be interpreted in multiple ways. Some view her as a jealous sister, angered by Inanna’s audacity and beauty. Others see her as the stern guardian of the Underworld, enforcing its immutable laws against even the mightiest of gods.

Ereshkigal is not merely a tyrant, however. Her rulership is marked by the somber duty of maintaining the balance between life and death. The Underworld, though grim, is a necessary part of existence, and Ereshkigal’s role is to ensure that this balance is respected.

Her complexity is further highlighted in her interactions with Nergal, the god of war and plague. According to one myth, Nergal is sent to the Underworld to apologize to Ereshkigal for an earlier slight. The two eventually become lovers, and Nergal stays with her, sharing her throne. This union suggests a softer side to Ereshkigal, one capable of love and partnership.

The Symbolism of Ereshkigal

Ereshkigal’s domain and her character are rich in symbolism. As the Queen of the Underworld, she embodies the inevitable aspect of death, a force that even gods must reckon with. Her stern, unyielding nature reflects the harsh realities of mortality and the unchangeable laws of the cosmos.

Her contrast with Inanna/Ishtar highlights the duality present in many mythological traditions: the interplay of life and death, joy and sorrow, creation and destruction. This duality is crucial in understanding the Mesopotamian worldview, where deities often personify natural and existential forces.

The Underworld and Its Inhabitants

Ereshkigal’s Underworld is depicted as a bleak and desolate place, where the dead lead a shadowy existence, devoid of the pleasures and pains of earthly life. This depiction aligns with the Mesopotamian belief that death was a somber and inevitable destination, lacking the promise of paradise or eternal damnation found in other mythologies.

The dead are bound by strict rules and overseen by Ereshkigal and her attendants. Among these attendants are the Anunnaki, judges who ensure that the dead receive their due treatment, and Gallas, demons who enforce Ereshkigal’s will.

Rituals and Worship

Worship of Ereshkigal was not as widespread or joyous as that of other deities like Inanna. Given her association with death and the Underworld, her cult was more somber and reserved. Offerings to Ereshkigal often included prayers for the dead and rituals to appease her, ensuring the safe passage of souls to the afterlife and protection from her wrath.

Priests and priestesses dedicated to Ereshkigal would perform these rites, often in temples that doubled as necropolises, bridging the gap between the world of the living and the dead. These rituals underscored the importance of respecting the dead and acknowledging the power of the Underworld’s queen.

Ereshkigal in Literature and Art

Ereshkigal’s presence in ancient Mesopotamian literature and art is significant, though less prominent than that of other deities. She appears in various myths and epics, including the “Epic of Gilgamesh,” where the hero seeks out Utnapishtim and learns of the bleak existence that awaits him in the Underworld.

Artistic depictions of Ereshkigal often show her as a stern, majestic figure, sometimes accompanied by symbols of death and the Underworld. These images reinforce her role as a powerful and fearsome deity, one who commands respect and awe.

The Legacy of Ereshkigal

The legacy of Ereshkigal extends beyond ancient Mesopotamia. As a fundamental figure in one of the world’s earliest and most influential mythologies, she has left an indelible mark on the cultural and religious landscape.

Her story resonates with the universal human experience of confronting mortality and the mysteries of the afterlife. Ereshkigal’s stern yet necessary role in the cosmic order offers a profound reflection on the nature of death and the enduring balance between life and the hereafter.

Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Underworld, stands as a powerful symbol of the inevitability and mystery of death. Her reign over the shadowy realm of the dead, her complex interactions with other deities, and her embodiment of the harsh realities of mortality make her a figure of profound depth and significance.

Her story, woven into the fabric of Mesopotamian mythology, continues to captivate and inspire, reminding us of the ancient world’s rich understanding of life, death, and the eternal balance that governs all existence.

References

- Black, Jeremy, and Anthony Green. Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. University of Texas Press, 1992.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944.

- Leick, Gwendolyn. A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology. Routledge, 1991.

- Wolkstein, Diane, and Samuel Noah Kramer. Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth. Harper & Row, 1983.

- Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild. The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. Yale University Press, 1976.