For over four thousand years, a group of enigmatic deities known as the Anunnaki have loomed large in the mythology of Mesopotamia—the cradle of civilization. Their presence echoes through Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian texts, appearing as judges, creators, lawgivers, and divine architects who shaped both heaven and earth.

No other pantheon has inspired such a fascinating blend of scholarly inquiry, religious interpretation, and modern speculation. The Anunnaki have been called everything:

- the children of the sky-god Anu,

- the earliest gods of civilization,

- divine rulers,

- keepers of destiny,

- in modern pseudoscience, there are even claims about ancient astronauts who allegedly engineered human evolution.

But who were they really?

To answer this question, we must travel deep into the ancient world—to the river plains of southern Iraq, where humanity’s first cities rose, and the earliest written myths were pressed into clay tablets. There, in the dim halls of temples and palaces, the story of the Anunnaki begins.

The World of the Sumerians: Where the Anunnaki Were Born

The Sumerian civilization flourished more than 5,000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia, a land that later civilizations would call the “birthplace of writing, astronomy, mathematics, and kingship.”

The Sumerians believed the universe was governed by a complex hierarchy of gods, each controlling specific forces of nature, aspects of society, and elements of human existence. At the top of this divine hierarchy stood the Anunnaki.

Who were the Anunnaki?

The word Anunnaki (or Anunna) likely means:

- “The princely offspring of Anu,”

- or “Those of royal seed.”

They were the children of Anu, the supreme sky god who dwelled in the highest heaven. As such, the Anunnaki represented cosmic authority, functioning as heavenly administrators of the universe.

They were not a small group but rather a collective of gods—sometimes seven, sometimes hundreds—depending on the text, era, or region.

The Role of the Anunnaki in Mesopotamian Cosmology

In early Sumerian texts, the Anunnaki functioned as:

- Judges of the cosmos

- Creators of human destiny

- Arbiters of life, death, and natural order

- Divine administrators responsible for maintaining me (universal laws)

They met in divine councils to decide the fate of gods and mortals alike.

Some Anunnaki resided in the heavens, others on earth, and many were associated with the underworld, where they served as judges over the dead.

This complexity mirrors the political and social reality of ancient Mesopotamia: a world of city-states, priest-kings, and councils of elders—cosmic governance reflecting earthly governance.

Creation: How the Anunnaki Formed Humanity

The most fascinating and enduring myth involving the Anunnaki is the creation of humanity. The fullest descriptions appear in texts like the Atrahasis Epic and the Enuma Elish.

1. Before Humanity Existed: The Gods Worked the Land

In the beginning, the gods themselves performed manual labor:

- digging irrigation canals,

- maintaining the fields,

- raising the land from marsh and river.

The younger gods, known as the Igigi, began to suffer under the endless toil.

Eventually, they rebelled—storming the home of Enlil, demanding relief.

2. The Divine Solution: Create Workers

A council of the Anunnaki convened to solve the crisis.

Their decision?

Create a new being who would perform agricultural and ritual labor on behalf of the gods.

Enki (called Ea in Akkadian), the god of wisdom and creation, proposed the method:

“Let us create a human from clay and the flesh of a god.”

A minor god—often the rebellious deity Geshtu-e or Kingu—was sacrificed, and their divine essence was mixed with sacred clay from the depths of the earth.

3. The Result: Humanity

Humans emerged as a blend of:

- divine spirit,

- earthly matter,

- and cosmic purpose.

This mixture gave humans the capability to understand divine order while fulfilling earthly responsibilities.

The Anunnaki and the Great Flood

The Flood Myth, famously paralleled in the story of Noah, also appears in the Atrahasis Epic and the Epic of Gilgamesh.

In these myths:

- Humans became too noisy or too numerous, disturbing the gods.

- Enlil decided to exterminate humanity with a massive flood.

- Enki, sympathetic to humans, secretly warned Atrahasis (or Utnapishtim) to build a boat.

The Anunnaki played roles both in sentencing humanity and in mourning the devastation afterward.

This duality—both strict and compassionate—reflects the complex nature of ancient Mesopotamian divinity.

The Anunnaki in the Underworld

Not all Anunnaki dwelled in celestial realms.

Many served as judges in the underworld (Kur or Irkalla), where they evaluated the dead.

A famous example appears in The Descent of Inanna, where the goddess Inanna confronts:

“The seven judges of the Anunnaki, who fixed their eyes upon her with the gaze of death.”

These beings were impartial and often terrifying—symbols of cosmic law rather than benevolent deities.

Major Anunnaki Deities: The Core Figures

Although the Anunnaki include many gods, the most central are

1. Anu

- Supreme sky father

- Leader of the divine council

2. Enlil

- God of air, storms, rulership

- One of the most powerful and feared deities

- Often initiates major world-changing events

3. Enki (Ea)

- God of wisdom, creation, water

- Protector of humanity

- Bringer of civilization

4. Inanna (Ishtar)

- Goddess of love, war, justice

- Linked to Venus

- One of the most dynamic and complex deities in human history

The Anunnaki as Teachers of Civilization

Ancient texts credit the Anunnaki with the foundations of human progress:

- Writing (cuneiform) – given by the gods to humanity

- Agriculture and irrigation – described as divine gifts

- Mathematics and astronomy – celestial knowledge

- Kingship – said to be “lowered from heaven”

Enki, in particular, is portrayed as a patron of civilization, establishing the world’s first city, Eridu.

The Rise of Alternative Theories: Ancient Astronauts

In the 20th century, the Anunnaki entered pop culture through alternative interpretations—especially those by Zecharia Sitchin—claiming:

- The Anunnaki were extraterrestrials from the planet Nibiru

- They genetically engineered humans as worker beings

- Ancient temples were landing pads for spacecraft

Scholarly Response

Academic consensus overwhelmingly rejects these theories.

Reasons include:

- No ancient text describes spacecraft or extraterrestrial visitors

- Sitchin’s translations are widely disputed

- Cuneiform specialists find no linguistic basis for the claims

Still, these ideas persist because they offer imaginative explanations for:

- ancient science

- monumental architecture

- sudden jumps in human civilization

Symbols, Temples, and Rituals of the Anunnaki

Ziggurats: Sacred Mountains

The great temples of the Mesopotamian world—ziggurats—were believed to be the earthly homes of the gods.

They were built as:

- layered mountains

- stairways to heaven

- cosmic connection points

Cuneiform Tablets

Knowledge inscribed on clay was believed to carry the authority of the gods. Many tablets describe:

- offerings

- rituals

- hymns

- divine decrees

- myths

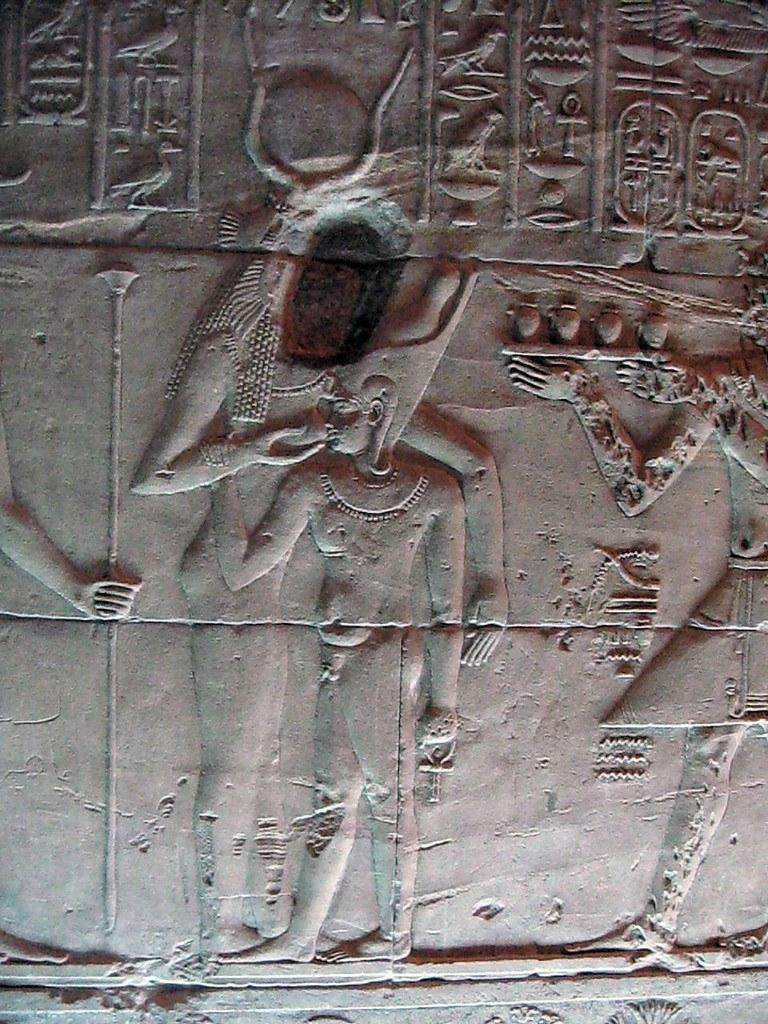

Sacred Animals and Symbols

Each major Anunnaki deity had symbolic attributes:

- Enlil – the horned crown

- Enki – flowing water and fish

- Inanna – the star of Venus

- Anu – the celestial sky-dome

These symbols appear in carvings, seals, and ancient art across the region.

Why the Anunnaki Fascinate the Modern World

1. They are some of the earliest recorded gods.

Their stories predate Greek and Egyptian mythologies.

2. Their myths are fragmentary.

Missing or damaged tablets leave tantalizing gaps.

3. They blend cosmic order, creation, and judgment.

4. They resonate with universal questions:

- Who created us?

- What is our purpose?

- What existed before civilization?

Myth, Memory, or Metaphor?

The Anunnaki endure because they sit at the crossroads of myth, religion, history, and imagination.

Historically, they were:

- divine beings of the Sumerian pantheon,

- creators of humanity,

- judges of order,

- patrons of civilization.

Culturally, they shaped:

- Mesopotamian kingship

- law

- ritual

- the earliest recorded stories

Symbolically, they represent:

- humanity’s search for meaning

- the mystery of origins

- the cosmic forces governing existence

Whether one views the Anunnaki as literal gods, mythic archetypes, or symbolic expressions of early human consciousness, their legacy remains profound.

The Sumerians—one of the earliest civilizations on earth—crafted a complex divine world where the Anunnaki stood at the center. Their myths, preserved in clay for millennia, continue to fascinate scholars and storytellers alike.

In the end, the Anunnaki remind us of the timeless human desire to understand our place in the universe—and the enduring power of myth to shape that quest.

Sources & Citations

Primary Texts & Translations

- Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild. The Harps That Once… Sumerian Poetry in Translation. Yale University Press, 1987.

- George, Andrew. The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation. Penguin Classics, 1999.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. Sumerian Mythology. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972.

- Bottéro, Jean. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Secondary Scholarship

- Leick, Gwendolyn. Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City. Penguin Books, 2002.

- Black, Jeremy & Green, Anthony. Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. British Museum Press, 1992.

- Hallo, William W. & Simpson, William K. The Ancient Near East: A History. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971.

- Ringgren, Helmer. Religions of the Ancient Near East. Westminster Press, 1973.

On Modern Interpretations & Pseudoscience

- Sitchin, Zecharia. The Twelfth Planet. (Not academically endorsed but referenced for context.)

- Tsoukalos, Giorgio A., ed. Ancient Astronaut Theories. (For comparison with academic views.)

- Feder, Kenneth. Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology. Oxford University Press, 2020.